-

We argue that the philosophical essence of “competition” in economics and broader social affairs is a clash of alternative hypotheses as to what is really true.

-

Moreover, it is historically unprecedented as a technology that offers virtually no potential utility towards violent ends whatsoever, and yet high defensibility against violence.

-

Consider that prices emerge from action, and the truth of prices comes from experimentation. It is not dictated. It is discovered iteratively. Every transaction spreads knowledge, inching a price towards a better consensus, yet consensus itself is a moving target.

-

The power of prices is the process of dynamic discovery that underpins their emergence, not the fleeting consensus of a specific moment in time. The price is never right, but prices are as right as can be hoped for at that moment. Attempts to coerce prices without the ability to change the reality they communicate are, therefore, bound to run into trouble. And yet we do not seem capable to accept the truth of prices whenever it is inconvenient. To ensure that consensus can arrive at valid social truths, we require systems or institutions that withstand attempts at coercion and which tap into decentralized discovery.

-

We think that, fundamentally, the EMH is contradicted by the implications of value being subjective,

-

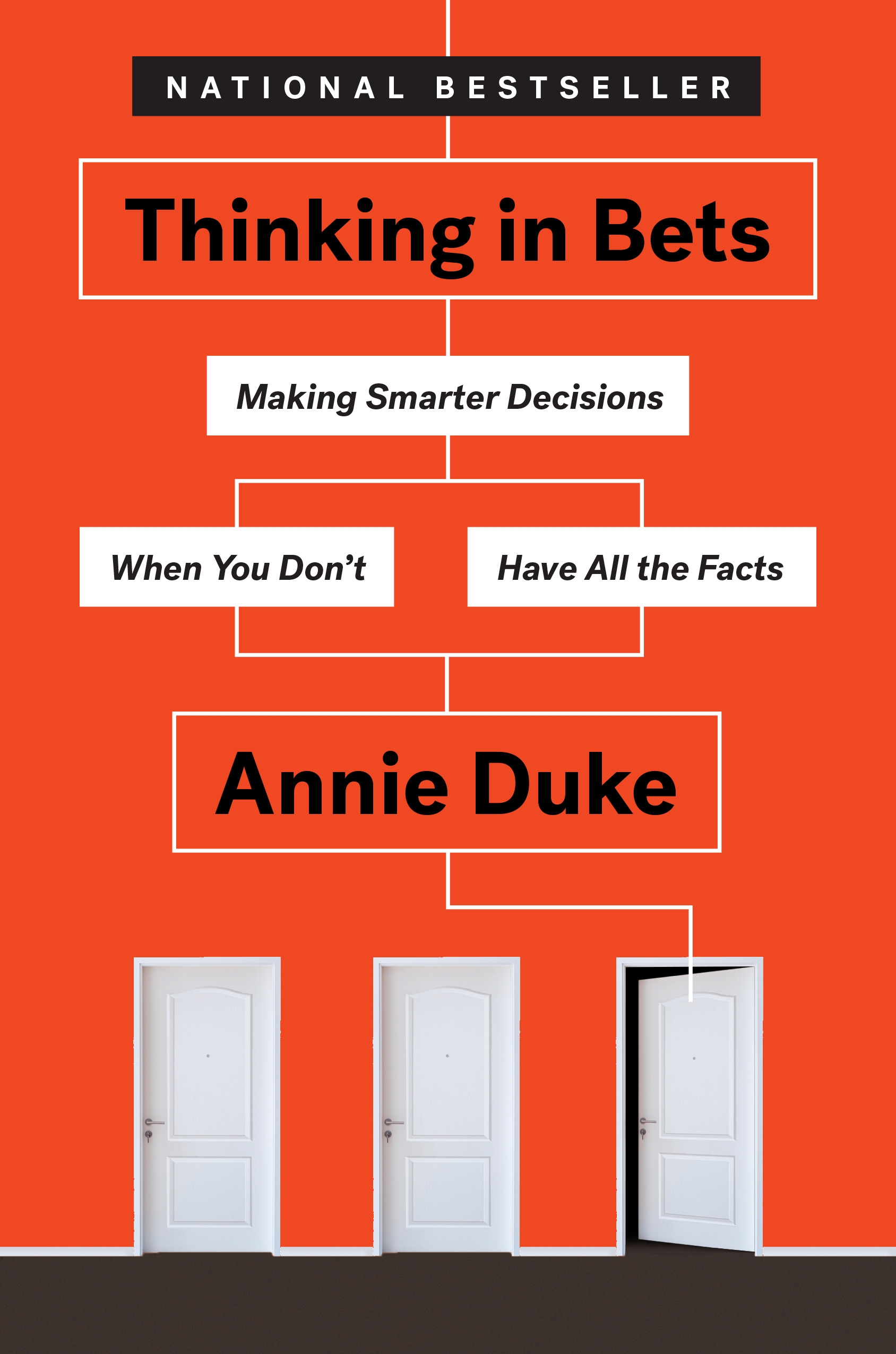

“Risk” characterizes a non-deterministic system for which the space of possible outcomes can be assigned probabilities. Expected values are meaningful and hence prices, if they exist in such a system, lend themselves to effective hedging. “Uncertainty” characterizes a non-deterministic system for which probabilities cannot be assigned to the space of outcomes. Uncertain outcomes cannot be hedged. The proposition is meaningless.

-

By “uncertain” knowledge, let me explain, I do not mean merely to distinguish what is known for certain from what is only probable. The game of roulette is not subject, in this sense, to uncertainty […] Or, again, the expectation of life is only slightly uncertain. Even the weather is only moderately uncertain. The sense in which I am using the term is that in which the prospect of a European war is uncertain, or the price of copper and the rate of interest twenty years hence, or the obsolescence of a new invention, or the position of private wealth owners in the social system in 1970. About these matters there is no scientific basis on which to form any calculable probability whatever. We simply do not know.

-

The subjective valuations on which its success depends are revealed by the experiment, and you can’t repeat the experiment pretending you don’t now know this information.

-

The investor better intuited the subjective values of future consumers than did the average market participant. Very likely they justified this on the basis of a heuristic or two. They staked capital on this bet — which was not risky and random but uncertain and unpredictable — and exposed themselves to a payoff that turned out to be huge, because they were right!

-

The most unfortunate aspect of this use of the term “competition”; is of course that, by referring to the situation in which no room remains for further steps in the competitive market process, the word has come to be understood as the very opposite of the kind of activity of which that process consists. Thus, as we shall discover, any real-world departure from equilibrium conditions came to be stamped as the opposite of “competitive” and hence, by simple extension, as actually “monopolistic.”

-

In making sense of this, we have to assume some kind of “function” from the space of information to price. We think it is acceptable to mean this metaphorically for the sake of exposition, without implying the quasi-metaphysical existence of some such force. We might really mean something like, the market behaves as if operating according to such and such a function or, such and such a function is a reasonable low-resolution approximation of market dynamics. Adam Smith’s famed invisible hand is an instructive comparison. For the time being, we will talk as if some such function exists. We can maybe imagine information as existing as a vector in an incredibly high-dimensional space, at least as compared to price, which is clearly one dimensional. We could even account for the multitudes of uncertainty we have already learned to accept by suggesting that each individual’s subjective understanding of all the relevant factors and/or ignorance of many of them constitutes a unique mapping of this space to itself, such that the true information vector is transformed into something more personal for each market participant. Perhaps individuals then bring this personal information vector to the market, and what the market does is aggregate all the vectors by finding the average.[32] Finally, the market projects this n-dimensional average vector onto the single dimension of price. If you accept the metaphorical nature of all these functions, we can admit this model has some intuitive appeal, in the vein of James Surowiecki’s The Wisdom of Crowds. The problem is that this is clearly not how anybody actually interacts with markets. You don’t submit your n-dimensional information/intention vector; you submit your one-dimensional price. That’s it. The market aggregates these one-dimensional price submissions in real time by matching the flow of marginal bids and asks.

-

Perhaps ironically, this points to the only sensible way in which markets can be called “efficient.” They are efficient with respect to the information they manipulate and convey: As a one-dimensional price, it is the absolute minimum required for participants to interpret and sensibly respond. Markets have excellent social scalability;[33] they are the original distributed systems, around long before anybody thought to coin that expression.

-

Provided with information, individuals can, and do, produce a price. But given a price, nobody — never mind a third-party observer or even the entire market — can (re)produce the information that created it. And this is the whole point. The “function” from information to price is not random, not ill-defined, and certainly not an “aggregation.” Rather, it is a very specific kind that serves a very specific purpose: It is the perfect compression of economically relevant information. It strips the noise of subjective values, preferences, and interpretations of reality down to pure objective signal, the same for everybody, and hence that the algorithm of the market can aggregate, entirely indifferent

-

engaging with markets requires individuals to compress the economic signal nascent in the n-dimensions of their information, heuristics, judgments, and stakes, and project it onto the single dimension of price, and that markets do not project the aggregates; they aggregate the projections.

-

One thing we especially like about Lo’s approach is his idea of “evolution at the speed of thought,” often rhetorical as much as anything else. We think this provides a useful conceptual tool to deal with what we deemed to be the only consistent deficiency in the material we covered on complex systems: Arthur, Holland, et al., seem to us so focused on the comparison to biological evolution, and on shifting the comparative conceptual framework from physics to biology as a whole, that they forget the role of purposeful human beings in all of this. Economic “mutation” is not random, it is creative, intuitive, and judgmental. It happens at the speed of thought because humans think on purpose. They do not cycle through the space of every thought that can possibly be had until they hit on one that happens to be a business plan.

-

genes mutate, but humans think.

-

At the heart of capitalist growth, however, is not the mechanistic homo economicus but conscious, willful, often altruistic, inventive man. Although a marketplace may work mechanically, an economy is no sense a great machine. The market produces only the perfunctory denouement of tempestuous drama, dominated by the incalculable creativity of entrepreneurs, making purposeful gifts without predetermined returns, launching enterprise into the always unknown future. The market is the conduit, not the content; the low-entropy carrier, not the high-entropy message. Capitalism begins not with exchange but with giving, not with determinist rationality but with creation and surprisal.

-

Information theory is the nemesis of those who would reduce markets to material laws. As manifestations of the interplay of human minds, markets are more analogous to biological phenomena. As the controlling knowledge of economics resides deep inside the companies that make up the market. You cannot predict the future of markets or companies by examining the fractal patterns of their previous price movements. There is no information there.

-

Value is subjective, which means uncertainty governs all economic phenomena. This creates a complexity that resists equilibria and is constantly changing besides. Within such a system, prices convey the minimal possible information necessary for economic agents to purposefully react. They do so with judgment and heuristics, not “perfect information,” which is nonsensical, as is “perfect competition” and “rational expectations.” For these reasons, prices may pass statistical tests for randomness, but they are not themselves random (although it is plausible that their randomness is random, and that randomness is random, and so on) but rather are unpredictable on the basis of market data alone. They are, however, predictable to the extent that the predictor accurately assesses the future subjective valuations both of economic agents and fellow market participants, and backs up this prediction with staked capital. This act of staking changes the uncertainties at play, rendering any attempt at genuinely scientific analysis futile. You can beat the market, it’s just hard, and it depends on understanding people, not data. And it’s meaningless if you do it in theory but not practice.

-

this it is, of course, not intended to infer that some rational and distinct meaning cannot be expressed through the word “capitalism,” but simply that it is far too often made an excuse for muddled thinking.

-

“The ideology of modern finance replaced the capitalist’s appreciation for free markets as a context for human creativity with the worship of efficient markets as substitutes for that creativity. The result was a divorce of entrepreneurial knowledge from economic power.”

-

Goods that are used to create consumable goods are a form of capital,

-

Capitalism — an economic system respecting and encouraging the nurturing, replenishment, and growth of capital — thus requires a delicate balance of the extremity of social interdependence. We must not be so loosely connected as to be unable to form no nascent markets in which capital can be made more or less liquid, but not so tightly connected as to disallow differentiation in these markets. People need to agree enough to be able to trade but also disagree enough to be willing to trade. The consensus enabled by price discovery in a market really is a discovery, not rhetorically, but in fact: It is a distributed discovery of a social truth. Individuals do not find their own private truths in isolation, nor is a politically correct truth dictated and imposed on all. Price is the maximally compressed signal of economically relevant information. Entrepreneurs react to what information they think might be captured by the signal — what about broader economic reality they think this signal might mean — by manipulating whatever capital they can bring under their control.

-

The obsession with GDP growth that fuels financialization also leads us to forget that inventing new things to produce tomorrow is as important, if not more so, than increasing what is produced today. So-called capitalists in such a regime can resemble the Soviet Union apparatchiks who focused exclusively on increasing output at the expense of managing the inputs or improving the quality of anything produced. Since the value of genuine innovation can’t be measured, it tends to be discarded in a world focused exclusively on forever increasing such meaningless statistics as GDP and stock market capitalizations with no understanding of why these numbers ought to go up. In many ways it is like a cargo cult: When good things happen, stocks go up — so stocks going up must be a good thing!

-

Larry White says of those who deny by definition that such a thing can even happen that they, “Are only looking at the blackboard and not at what is happening outside the window.”[63] Bitcoin doesn’t feel like it makes sense, and it is nowhere to be found in the textbooks, therefore it doesn’t. This is a curious approach to understanding novel phenomena, that, in general, we would not recommend. Reality doesn’t care how you describe it.

-

If a start-up then came along, people might well say, “That’s not a business because it doesn’t make a profit,” or “That’s not a business because it doesn’t have a defined business plan.” Clearly, this would be ill-advised. That is not to say that their models and definitions would be perfectly wrong instead of perfectly right, but rather that things are not so binary. Reality is messy, and it is reality we should care about, not our theories of reality that, it turns out, have never really been tested.

-

What this shows is that a “double coincidence of wants” that makes barter untenable at any worthwhile scale has little to do with “convenience” and is first and foremost a product of knowledge. We can only have a limited appreciation of others’ valuations, and this appreciation diminishes the further removed from us they are in circumstance and in time. And note, this includes our future selves: We do not know for sure what we will value in the future because we do not know what will happen to us in the future. Money is useful to us because of economic uncertainty: Our fundamental inability to know much at all about what all others think and about what is going to change.

-

Humans act in ways that make sense to them. This simple axiom is practically a tautology and is certainly at least obviously true from experience, and yet contemporary academic economics has somehow contrived to ignore its consequences: A human being necessarily understands what they are doing, but another human being almost certainly does not understand what the first is doing; in most cases will not, and in many cases cannot.

-

loop you go. The entirety of the chain of prices across all exchanges is shown to be a series of independent and real-time decisions about how to value one’s own time and

-

the entrepreneur does not, cycle through the space of every thought that can possibly be had until they hit on one that happens to be a business plan. That is to say, the creation of capital is not a mathematical or a probabilistic exercise. It requires creativity, intuition, and judgment. It requires a theory of mind and an empathy for the subjective preferences of others.

-

is worth being as clear as possible that money is not capital. Money is the right to time entirely in general. It is liquid and fungible. Capital is time that has been crystallized towards a specific end.

-

As for the incumbent, they might worry its highly dilutive mechanism could not be trusted at all; that the capital formation it supports is toxic and unstable; that its overall operation is highly uncertain and that, as this perception seems to be spreading, its long-term utility and the size of its network is in increasingly serious question. They might reason that, like Esperanto, its elaborate design may make it pleasing to its designers yet fragile and encumbered in the real world, whereas natural languages and natural moneys emerge and evolve to fulfill a decentralized demand.

-

The Semantic Theory of Money we satirically articulated in Chapter Four has a spiritual counterpart here: That by all manner of semantic contortions, we can convince ourselves that we can consume more than we produce, reap more than we sow, borrow more than we repay. As Ludwig Wittgenstein said in Philosophical Investigations, “philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.” Let us not be so bewitched

-

The tricky thing about growing the capital stock is that it is by its nature an uncertain process. It cannot be automated, nor reduced to an algorithm. It is necessarily experimental. New capital is as much discovered as invented. This is why money is so important to efforts to create capital: These efforts themselves take time and energy that might otherwise have gone towards more certain avenues of production. Only some small group may have the knowledge and skills to credibly experiment with creating a particular new tool or new organization, and they may not be willing to take the risks required. Some other group may have the willingness to take the risks but not the knowledge or skills to do so. Money provides a means for coordinating the risks of attempting to create capital such that those contributing to the risk taking are not necessarily those bearing the risks.

-

To start with, the oversupply of debt forces the price of debt down to clear the market.[81] The ranking of experimental viability that the market might have carried out to allocate scarce capital becomes irrelevant and all prospective experiments are carried out. This juncture is key. These experiments are, by their nature, uncertain. The price of the capital they would faithfully attract can hardly be better described than a crowd-sourced best guess as to their risk relative to the opportunity set. It is possible that these guesses are conservatively false and that all will succeed. But it is likely that more bad experiments will fail than would have otherwise, hence more debt will tend to mean more bad debt.

-

A risky entrepreneurial endeavor making a return below this inflation rate will no longer be creating wealth for its owners but losing it — not as fast as holding fungible pan-bank liabilities (money), admittedly, but then money on its own is thought to have no risk. The point of the risk of entrepreneurship is to get a real return. Hence all return-seeking capital assets are unnaturally incentivized to lever up to stay ahead of inflation. Of course, all that is really happening here is that by swapping equity for debt, the experiments themselves are forced to become riskier than they ought to be.

-

In a highly centralized and industrialized food-supply system there can be no small disaster. Whether it be a production “error” or a corn blight, the disaster is not foreseen until it exists; it is not recognized until it is widespread. By contrast, a highly diversified, small-farm agriculture combined with local marketing is literally crisscrossed with margins, and these margins work both to allow and encourage care and to contain damage.

-

money is useful not because it fits some or other semantic scheme that holds up if and only if nothing in real life changes, but because real life does change, and money provides certainty in an uncertain world. But this is not to say that uncertainty is harmful. Capital formation is by necessity highly uncertain but greatly beneficial. Money provides a means of socially scaling the embrace of this uncertainty, provided it gives us certainty in the first place.

-

Software is productive capital for which the raw ingredients are coherent human thoughts.

-

amount of money lent to a government, and the interest amount charged, is assumed to be risk-free because it is in turn assumed that a government can tax, borrow, or print further amounts of money to pay its debt. These three options are indeed available to a modern government, but one must not ignore the fact that the government has no access to risk-free rates of return when investing the borrowed money. The above-mentioned options are in fact nothing more than means of passing on the bill to others when the fact of a non-risk-free

-

Frederic Lane and Reinhold Mueller note in Money and Banking in Medieval and Renaissance Venice that “both ‘medium of exchange’ and ‘standard of value’ are sufficiently ambiguous to make ‘moneyness’ a matter of degree,”

-

The heart of the claim, when stripped of emotional resonance, is that money, via capital, enables individuals to better be a part of the whole; to behave more responsibly, to contribute more effectively, and to make choices more purposefully. These cannot be effectively dictated top-down.

-

A complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked. The inverse proposition also appears to be true: A complex system designed from scratch never works and cannot be made to work. You have to start over, beginning with a working simple system.

-

In fact, the Internet Protocol suite[138] are all free and open source. However, to return to Lessig, these are minimalistic and push complexity to the edge of the network. Few can be described as “applications,” and those that can are extremely simple. None are expected to add “new features” with any regularity whatsoever. They are explicitly intended to be building blocks for further applications, and so necessarily tolerate network congestion as a trade-off to remain open. This minimalism aids consensus formation. Notice that for a potentially complex pseudo-protocol, management by a centralized private party elegantly solves many of the problems raised thus far. Identity can be centrally issued and authenticated. The complexity of the application can be arbitrarily high without incurring trade-offs in consensus, as users are merely clients. The application can be updated arbitrarily often and quickly for the same reason.

-

Scarcity, consensus, and identity are closely related. In the absence of scarcity, consensus is simply not required. But where scarcity exists, value exists, where value exists, markets exist, and market prices are a kind of consensus.

-

But … now we actually can pay in little chunks. Your humble authors have personally paid on the order of $0.03 for coffee, and even that was really just a gimmick as the coffee may as well have been free, but it could easily have been $0.003, $0.003c, or $0.000000003c. If you can pay $0.0003c online with next to no fees, why not pay $0.0003c per second to stream music? If you listen to Spotify three hours a day, that would come out at around $10 per month. And why stop at music and movies? Why not podcasts, too?

-

The idea that energy consumption is de facto bad, either for the environment or in general, is imbecilic and profoundly anti-human, and should not be accepted as an axiom of our support for Bitcoin, or any other technology that indisputably benefits humanity. Bitcoin does not

-

Bitcoin fixes this: This is no longer necessary, because Bitcoin is digital infrastructure that can be built out to natural generation sites at comparatively minuscule cost, and mining offers a clearing price for energy that requires no transmission costs.[157] It is our prediction that the mechanism just outlined will start to greatly reduce the financing costs and operational complexities of nuclear,

-

“leverage” in Chapter Three, This Is Not Capitalism, as “induced vulnerability to shocks in exchange for a magnified gain in their absence”:

-

Knowledge and competence are arguably the theoretical and practical sides of the same coin: the hard-won product of experience and discovery.

-

It is a peculiarly modern fantasy that civilization makes life easier: That it frees us from the shackles of a state of natural oppression and allows us all to find and to be our true selves. This is juvenile quackery. Civilization certainly makes life better, but earned at the cost of hard work. Civilization is proof of work. Civilization is the choice, as a community of individuals opting into voluntary cooperation to defer gratification: to invest rather than to consume. Individuals are perfectly free to opt out of these hard choices by returning to a pre-civilizational state, but it would be preferable to all if, in doing so, they had the decency to in fact remove themselves from civilization rather than skimming its consumable surplus while contributing nothing to its maintenance.

-

It is not as though the complaints from the left against the petroleum companies, the agribusinesses, the producers of GM crops, the developers, the supermarkets and the airlines were all based on fabrications, or as if these businesses can be run just as they are without any lasting environmental damage. In fact, the greatest weakness of the position that John Gray describes as “neo-liberalism” — the ideological summoning of the market, as the sole remedy to all social and economic problems — is the refusal to make the distinction, apparent to all reasonable people, between big business and little business. When businesses are big enough they can cushion themselves against the negative side effects of their activity, and proceed as if all objections could be overcome by a consultant in “Corporate Social Responsibility,” without any change in the way things are done.

-

As was detailed in Chapter Six, Bitcoin Is Venice, government that big — and, in particular, that indiscriminately wasteful and destructive on account of its bigness — will not survive a Bitcoin standard. Bitcoin is the negative feedback that forces it to reckon with its own unsustainability. As Ostrom, Scott, and Scruton would have recommended all along, government and business alike will be forced to become far more local, contextual, knowledgeable, and competent.

-

Capital is whatever can be transformed or used to produce goods that satisfy human wants.

-

capital is, like value, entirely subjective. We call capital that which we use in the process of creating a good. Milk may be the good which will satisfy our want for a beverage, but it can also be the capital which we can use to produce a cake which will satisfy our hunger. Capital is thus an abstract idea we superimpose on reality to describe things which have subjectively useful potential energy

-

Our imagination and recognition of objects, concepts, or associations as capital makes them such. To see is to create. At the core of forming and accumulating capital is our ability to mutually recognize and agree on its existence and to record it such that there is an accessible consensus for consultation and resolution of dispute.

-

Cooperation is necessarily sacrifice for the very simple reason that people are different. They have different experiences and they want different things, not only of the available scarce resources but, even more irreconcilably, of each other. Cooperation over a period of time greater than this very moment likely requires a promise, which is a sacrifice of that agent’s own future wants and preferences, which by then may have changed.

-

Returns are never guaranteed as all economic activity is fundamentally uncertain, and savers hoping for a return must turn their liquid money over to an entrepreneur. The act of transforming liquid, fungible money into illiquid, nonfungible capital is anti-entropic.

-

The entrepreneur does work in suffusing money with her creativity and agency to transform disorder into order. But she does so specifically and locally. She has a purpose and a goal in mind. One can save in general but one cannot invest in general. One must invest in something.

-

A dictator may be a social planner — and may even be a highly competent and effective social planner, in the short run — but he is not a social capitalist. Throughout history, humans’ ability to create social capital has always been linked to de Soto’s understanding of capital as fundamentally being an idea: a layer of abstract consensus by which humans subjectively contextualize objective reality.

-

The shift to architectural central planning (among many other equally awful varieties) after the Second World War was precipitated by three major developments: the spread of mass manufacturing, the rise of the automobile, and the success of exactly this mode of planning during the war.[187] Taken together, these forces remolded man’s relationship with urban space. The automobile blurred the landscape into a green haze onto which we did not mind imposing industrial-scale monotony. Developments became grand affairs that fit in an even grander vision. The aesthetic dreams of intellectuals replaced the varied tastes of people.

-

Just as planned economies suffer from an inability to tap into distributed knowledge, planned cities ignore the reality on the ground.

-

He conceived of good planning as a series of static acts; in each case the plan must anticipate all that is needed and be protected, after it is built, against any but the most minor subsequent changes. He conceived of planning also as essentially paternalistic, if not authoritarian. He was uninterested in the aspects of the city which could not be abstracted to serve his utopia.

-

“Breathe, breathe in the air. Don’t be afraid to care,” we hear on the opening song of Pink Floyd’s magisterial The Dark Side of the Moon. A parent gives their newborn the

-

Paul Graham gives a more socially motivated explanation of essentially the same issue in the essay, Hackers and Painters, and with a potent punchline: Everyone in the sciences secretly believes that mathematicians are smarter than they are. I think mathematicians also believe this. At any rate, the result is that scientists tend to make their work look as mathematical as possible. In a field like physics, this probably doesn’t do much harm, but the further you get from the natural sciences, the more of a problem it becomes. A page of formulas just looks so impressive (Tip: for extra impressiveness, use Greek variables.) And so there is a great temptation to work on problems you can treat formally, rather than problems that are, say, important.

-

Scott’s general criticism of high